As Intel, Samsung, TSMC, and others move ahead with plans for new computer chip development and manufacturing plants in the US, those efforts are running into a new headwind: there aren’t enough people with the skills needed to run the facilities.

“The competition for talent is fierce,” said Cindi Harper, vice president of Human Resources, Talent Planning and Acquisition at Intel. “It’s also a candidate’s market, meaning the demand for talent is greater than the current supply.”

“There’s a shortage of semiconductors and people to make them,” said Mark Granahan, co-founder and CEO of iDEAL Semiconductor, a five-year-old fabless chip start-up in Allentown, Pennsylvania. “It’s not like there’s a specific type of person or function missing. It’s across the board.”

The skills gap is exacerbating a chip supply shortage that predated disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic — but the pandemic made matters worse. Older semiconductor fabrication plants were already running at maximum capacity, according to Alan Priestley, a vice president analyst at Gartner Research. “COVID exacerbated the problem because all the demand forecasting for the industry was thrown into the air,” he said in an earlier interview.

Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and others have been lobbying the US government to increase domestic chip production, citing problems overseas that have hampered hardware production. In fact, a US Commerce Department report in January said the chip shortage is so bad that at one point in 2021 there was just a five-day supply worldwide — with no sign the situation would improve anytime soon.

That, according to US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, leaves auto manufacturers and other chip users with “no room for error. It’s alarming, really, the situation we’re in as a country, and how urgently we need to move to increase our domestic capacity,” she said while presenting her agency’s findings.

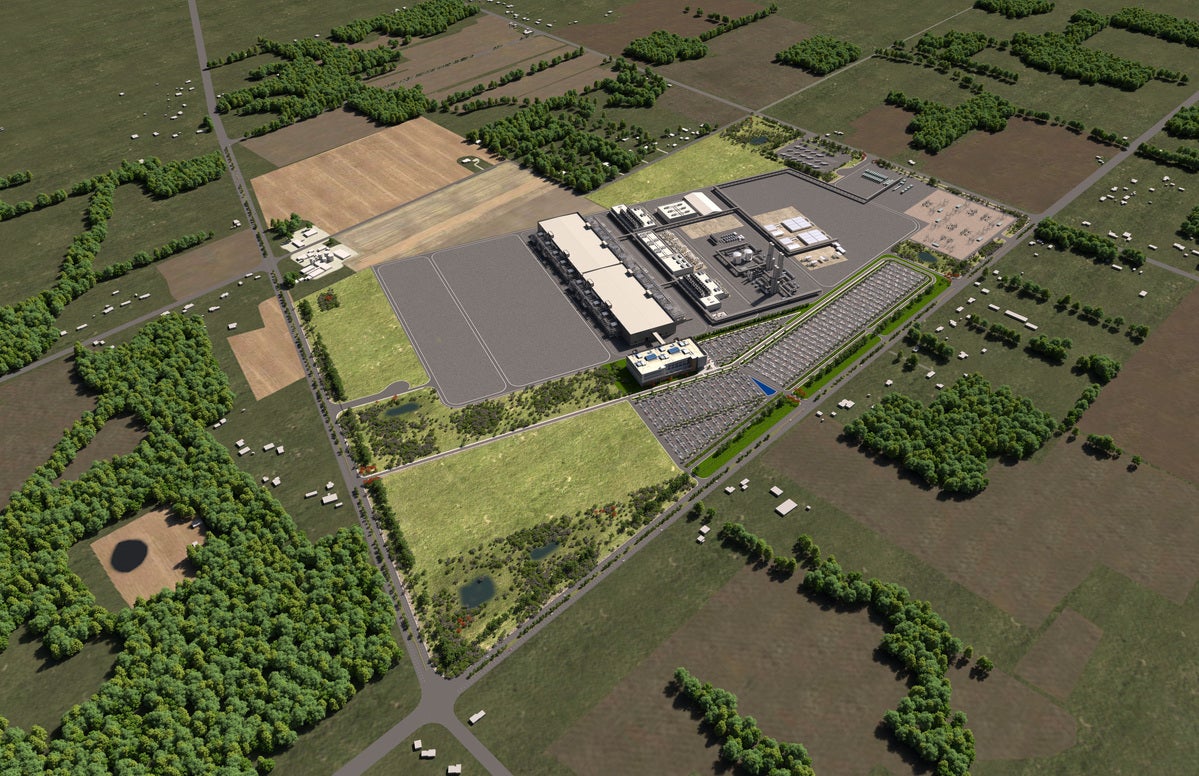

A rendition of one of two semiconductor fabrication plants Intel plans to build in Ohio.

But new plants need skilled workers. Granahan, who hopes IDEAL can start operations this fall, said it took him a year of searching the world to find one PhD-level engineer; it took another nine months to get a visa to bring the worker from Europe to the US.

“This country overall could do itself a lot of good if it had an aggressive legislative agenda to bring more talented STEM individuals into the country,” he said. “We’re probably not unique there. I’m sure Intel, Apple, Microsoft, and Qualcomm are all facing the same issues.”

STEM education programs key

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) job openings are poised to grow 11% from 2020 to 2030. But China has already surpassed the US in the number of advanced STEM degrees its students earn annually. In light of that, the US will need to complement domestic workforce education with reforms to expand high-skilled immigration, according to the Institute for Progress, a Washington-based research and STEM education advocacy organization.

Through complacency, the US has let its immigration system collapse under the weight of growing backlogs, “interminable wait times,” and unpredictability, according to Jeremy Neufeld, a senior immigration fellow at the Institute for Progress.

“We haven’t updated the caps on immigrant visas in 30 years, and it’s increasingly causing global talent to look abroad, all while crippling the ability of startups and other cutting-edge firms to draw on the best and brightest from around the world to push out the technological frontier,” Neufeld said via email.

US legislators should be working to ensure the industries at the cutting edge of research have reliable and predictable access to talent, which is all part of keeping the US ahead of China, he said. Among many other measures, the US House version of the Bipartisan Innovation Act (BIA) includes key provisions to lift caps for STEM Master’s degree and PhD holders if they work in critical security industries. But it’s not clear that provision will survive the congressional negotiations with the Senate.

One of two semiconductor fabrication plants Intel is building in Ohio.

Another promising option would be to exempt international graduates with advanced STEM degrees from the hard caps “that are devastating our ability to recruit talent,” Neufeld said.

“In the US semiconductor manufacturing industry, 75% of STEM PhDs are born abroad, and we’re already seeing engineering talent shortages causing delays for new plants to get up and running, which will only get worse if Congress spends billions on subsidies without addressing the hard talent bottlenecks,” Neufeld said.

While technology bootcamps and accelerated computer science degree programs are expanding throughout the world to meet marketplace demand, many positions at fabrication plants require experienced workers.

“Certainly, hiring younger folks or recent graduates is a path if there were enough of them,” Granahan said. “I’m a startup company. I have to fill every function in the company, whether sales and marketing, applications and systems, or engineering. All these things require some technical background to do. We need more two-year degrees, Master’s degrees, and PhDs. Focusing in one area is not a bad thing, but we need a broad brush of things.”

The falling US market share for chips

The US share of global semiconductor fabrication capacity has been on a steady decline for decades, according to the Congressional Research Service (CRS). US semiconductor production represented about 40% of the market in 1990; that dropped to around 12% in 2020.

While the US is not in last place in terms of global chip production — the European Union accounts for about 7% to 8% of production, and several other nations are even lower — but the US decline hasn’t abated.

“I think a practical scenario is first to at least maintain the current percentage as Asian countries continue to ramp up, and then the second phase would be for the US and EU to strategically identify areas for investment and increase share, while reducing reliance on Asia,” said Gaurav Gupta, a vice president analyst at research firm Gartner.

“This will take years and decades,” Gupta said. “Can US come back to the 35%-plus share? I don’t think so. We need more realistic expectations.”

One problem is that when chip manufacturing moved to Asia in recent decades, companies also developed a corresponding ecosystem that is very efficient and mature, Gupta noted.

Given the high costs and complexity of chip manufacturing, many US semiconductor firms transitioned to a “fabless” model, where the chips are designed here but fabricated abroad — mostly in East Asia. That region is now home to nearly 80% of global chip fabrication, according to the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS).

“Some of America’s largest tech firms, including Google, Apple, and Amazon, rely on Taiwan’s TSMC alone for nearly 90% of their chip production,” Gregory Arcuri, a CSIS research assistant wrote in a January blog.

According to a TSMC spokesperson, construction of TSMC’s 5nm fab in Arizona, “the country’s most advanced chip manufacturing plant,” is well underway and is on track with production targeted to begin in 2024.

Construction of TSMC’s 5nm semiconductor plant in Phoenix, Arizona is currently underway and scheduled to begin producing chips in 2024.

Upskilling and reskilling workers would help

While current semiconductor fab facilities are highly automated, they still require a lot of workers to be built, and engineers and engineering technicians to run them once they’re up and running.

With the right approach, the US could achieve a dramatic reshoring of chip manufacturing, according to a report by eightfold.ai, a tech talent management software vendor. Eightfold’s study last year found that through upskilling and reskilling workers, and with a focus on adjacent skills, chip manufactruing in the US could move ahead.

“By considering adjacent skills, we can upskill and reskill individuals with the potential to move from declining roles to rising roles. This can dramatically increase the pool of potential semiconductor talent,” the report said.

The report also recommended government policy changes, such as tax credits and other investments, that will help reshore the semiconductor industry, much of which is encapsulated in the CHIPS for America Act.

“…What we need is consistent support from government in terms of policies and incentives to encourage students to look towards the semiconductor industry and help companies recruit talent,” Gupta said. “Countries like Taiwan and China have had better policies in recent years.”

Government efforts stall

Government funding to help draw talent into the industry hasn’t made much progress — even though the Senate and House have both passed versions of the CHIPS for America Act. It’s designed to offer tax credits and other investments to help reshore the semiconductor industry. Despite bipartisan support, however, members have not reached consensus on funding the bill, according to Arcuri.

Another piece of legislation — the US Innovation and Competition Act (USICA) — passed the US Senate. It would provide $39 billion in financial assistance for fab plant construction, expansion, or modernization, but has stalled in the House.

Intel has been working to drive urgency around passage of funding for the CHIPS for America Act, Harper said.

“The CHIPS Act is designed to increase investment in the US, creating tens of thousands of jobs,” she said via email. “This partnership from the public sector is needed to level the playing field for US chipmakers so we can compete with foreign competitors in Asia who have a 30% to 40% cost advantage driven largely by their own significant government subsidies.”

Chipmakers are investing in new US plants

Intel has spent about $20 billion on the construction of two new Ohio-based chip factories aimed at boosting production to meet the surging demand for semiconductors. It is just one of a number of vendors, including Samsung, Texas Instruments, and GlobalFoundries that are planning to build or expand their semiconductor manufacturing presence in the US within the next three to five years.

“Irrespective of the shortages, Intel and other vendors need new fabrication plants to support the next generation of process nodes. As the U.S. continues to demonstrate its willingness to invest in semiconductor manufacturing, it is becoming an appealing market for such expansion,” Gartner’s Priestley wrote in a January blog post.

It’s not just the big chip makers. Smaller manufacturers are spending money, too. Last year, Wolfspeed (formerly Cree Inc.) opened a 200mm Silicon Carbide Fab in New York, and semiconductor maker GlobalFoundries announced plans to spend $1 billion to build a second New York factory to boost chip output.

Meanwhile, Intel is also working to address the issue of STEM education; it’s partnering with universities and community colleges and plans spend about $100 million over the next decade on new STEM programs. In addition to that investment, the US National Science Foundation fund will spend an additional $50 million for national opportunities.

“This means a total of $150 million will be available for semiconductor manufacturing education and research,” Harper said. “We’re also committed to helping build STEM talent starting with early education through secondary education — this is the best long-term strategy to address labor challenges.”

Copyright © 2022 IDG Communications, Inc.

Source by www.computerworld.com